Spinning

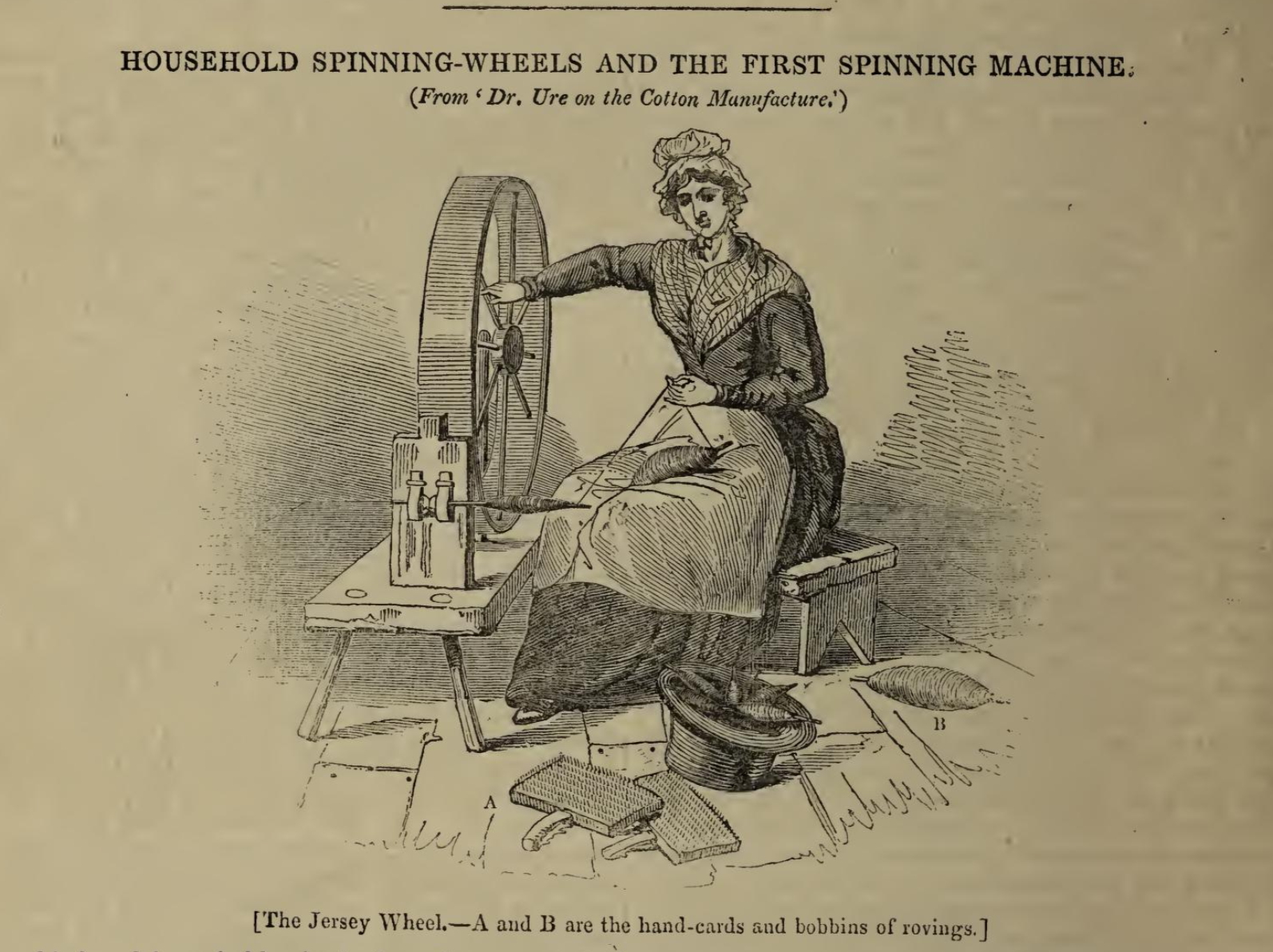

Homespun on the Southern Frontier: Everyday Cloth in a Changing World When we think of the early American frontier, images of log cabins, rugged landscapes, and self-reliant families often come to mind. If we imagine clothing, it might be dirty, worn, or ragged, conceptions shared by urban and literate populations of the time. Between the 1790s and the 1830s in the developing settlements of western Tennessee, northern Alabama, and eastern Arkansas, homespun was not simply a household necessity. Homespun yarn and cloth was a cultural marker that set frontier families apart from urban Americans and from the wider world. A Fabric of Necessity On the Southern frontier, store-bought fabrics were often hard to come by and perhaps more expensive than many could afford. Settlers often relied on home production to meet daily needs. Spinning wheels, looms, and dye pots were fixtures in most households. Memoirs from the region describe women weaving wool, cotton, and flax into cloth for everyday use. Loom houses, small outbuildings dedicated to weaving, were common across the countryside. Descriptions of these structures, and of the constant work inside them, appear repeatedly in family histories and personal narratives. These processes demanded skill and time. A family’s annual supply of clothing depended on the diligence of its spinners and weavers, both free and enslaved. The production of cloth was a form of survival labor, as essential as tending crops or raising livestock. Economic Variation in Homespun Not all homespun looked the same. Economic background shaped both the quality of cloth and the extent to which families relied on store goods. The equipment available in each household, the type of fibers at hand, and the skill of the family members, or enslaved workers, who produced the cloth all played a role in shaping how people dressed. Subsistence Farmers: Simple Tools, Practical Cloth For subsistence farmers, textile production was a task of necessity carried out with minimal equipment. A single great wheel for spinning wool or flax, a few hand cards, and a sturdy loom often housed in a shed or corner of a cabin were all that most families could afford. The products of these modest setups were coarse but serviceable: cotton-linen blends for everyday shirts, linsey-woolsey woven from wool and flax for winter garments, and clothing dyed with walnut hulls or other natural dyes readily available in the landscape. Probate records from western Tennessee in the 1820s often list “1 spinning wheel” or “1 loom” among the most valued household goods, underscoring how essential even a single set of tools was for survival. In Old Times in West Tennessee, the author recalled that “every man, woman, and child wore homespun,” a phrase that conveys both ubiquity and necessity for farming families. These were households where textile work consumed long hours and left little room for ornamentation. Middle-Tier Households: Blending Homespun with Store-Bought Families with modest surplus income often invested in more than one wheel, perhaps a flax wheel for fine spinning, a great wheel for wool, and a reel for winding yarn. Some kept a dedicated loom house on their property, a sign of both the volume of work being produced and the family’s relative prosperity. These households were still dependent on homespun for daily wear, but they might purchase a few yards of calico or factory cloth from a dry goods store in a nearby town. Brightly printed cottons or lighter muslins were often reserved for Sunday wear, children’s dresses, or trimmings on garments otherwise made from homespun. A memoir from the early settlement period of middle Tennessee describes young women working “by the firelight at the wheel,” while a loom in the outbuilding produced the family’s bed ticking and everyday cloth. These glimpses suggest a pattern: middle-tier households balanced the labor of spinning and weaving with a cautious use of store goods, investing money only where the most visible or socially important garments were concerned. Wealthier Settlers: Variety and Display Wealthier settlers, particularly those with larger landholdings or professional occupations, had access to a greater range of textile tools and the ability to employ others to use them. Inventories from these families sometimes list multiple looms, reels, and wheels, indicating that production was carried out on a larger scale. In many cases, enslaved women were tasked with spinning and weaving, producing cloth for both the family and the plantation workforce. These families could also afford imported fabrics. Dry goods merchants in river towns such as Memphis or Natchez advertised silks, satins, and fine woolens brought in by flatboat or wagon. Such cloth was used for dresses, coats, or other garments that signaled wealth and refinement. Yet even in prosperous homes, homespun retained a role. Servants and enslaved laborers were almost always clothed in domestically produced fabric, and family members might continue to wear homespun for work garments. An 1830s account from Bolivar, Tennessee, for example, notes the contrast between the “Sunday attire of imported calicoes” and the weekday reliance on “the strong home-woven stuff that never failed in service.” For wealthier settlers, the loom house remained a place of industry, but one that supported social display rather than mere survival. Homespun as Supplemental Income Across all economic classes, spinning and weaving could also serve as a means of generating extra income. Dry goods merchants frequently advertised their willingness to purchase homespun yarn or cloth, particularly when cotton was scarce in local markets. Women who produced more cloth than their families required could exchange it for credit or trade it for imported goods. This practice underscores how deeply textile work was integrated into the local economy. Homespun was not just a marker of domestic diligence, it was a form of currency. Wills and probate records listing spinning wheels, loom houses, and inventories of “homespun” make clear that cloth was treated as an asset, as valuable to the estate as livestock or tools.