Troubleshooting Difficult Fleece

How to Handle Common Fiber Issues at Every Step

Working with raw fleece is one of the most rewarding experiences for fiber artists. There's something magical about taking wool straight from the sheep and transforming it into soft, handspun yarn or felted art. But as with any craft rooted in nature, there are challenges that come with it. Whether you picked up a fleece from a small farm, a festival, or even a heritage breed project, chances are it will come with some imperfections. These issues may seem intimidating, but many can be managed or even turned into opportunities for learning and creativity.

In this expanded guide, we’ll walk through nine common fleece issues and explain how to approach them at each stage of the hand-processing journey: skirting, picking, scouring, combing or carding, and spinning. Along the way, we’ll touch on a few historical practices to give some perspective on how these processes have evolved over time.

Vegetable Matter (VM)

Vegetable matter includes bits of hay, straw, burrs, seeds, grass, and other plant debris tangled into the wool. This is especially common in fleeces from sheep that have not worn coats or lived in clean pasture conditions.

Skirting: In this first step, focus on removing sections of the fleece where there is more plant matter than fiber. Heavily contaminated sections, like those from the neck or britch, are usually better off discarded. Historically, subsistence farmers might have kept even the dirtiest fleece for stuffing mattresses or insulation, but for spinning, clean fiber was always prized.

Picking: Tease apart the locks to loosen debris. This step can be meditative but time-consuming. A fleece picker or just your fingers can help dislodge stubborn pieces.

Scouring: Ensure the fleece has enough room to open up in the water. Scour in loose bundles rather than tight mesh bags so that loosened VM can float free. Multiple rinses may be necessary.

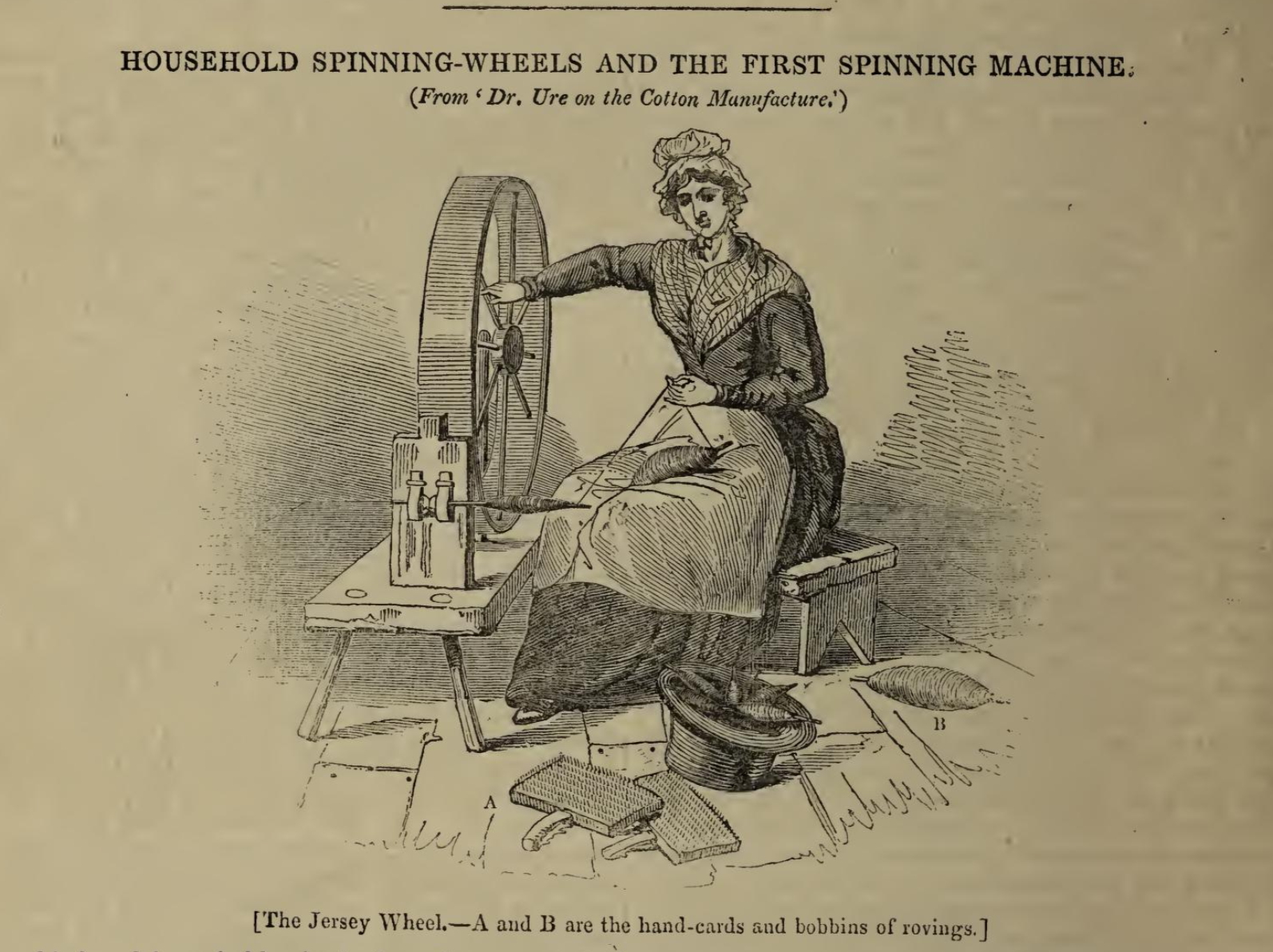

Combing/Carding: Flick each lock or use wool combs to remove any remaining debris. Combs are especially effective for removing fine VM, though they do waste more fiber. Historically, flick carders and wool combs were common tools in pre-industrial households. I prefer to take a lock at a time, twist it in the middle, then pass each half through my hand carder a few times. Then, flip it around and do the same thing again. This gets 90%+ of the VM out for me, and even though it takes a long time, I have had beautiful results with this method.

Spinning: If some VM remains, pick it out as you draft. It's not ideal, but workable. For rustic yarns, this might even add character.

Excessive Grease or Dirt

Lanolin is a natural grease produced by sheep, but some fleeces are more saturated than others, especially breeds like Merino. Dirt, dust, and suint (dried sweat) also contribute to a heavy, tacky fleece.

Skirting: If any part of the fleece feels particularly caked in dirt or unusually greasy, you might choose to remove it now. In older times, such wool might have been reserved for felting or discarded if too foul-smelling.

Picking: Open up the locks to allow detergent to penetrate the fibers more easily during washing.

Scouring: Use hot water (112°F or higher) and a strong wool-friendly detergent. Greasy fleeces often need several washes. Adding vinegar to the rinse water can help lift remaining residues.

Combing/Carding: If your fiber still feels waxy or sticky, it's not ready for carding. Grease can clog your tools and attract dust.

Spinning: If you attempt to spin greasy wool, you may find your drafting uneven or sticky. While some traditional spinners spin "in the grease," it should still be clean grease, not still dirty.

Breaks or Weak Spots

Breaks are weak points in the fiber, usually caused by stress, illness, poor nutrition, or lambing. They can cause yarn to fall apart if not handled properly.

Skirting: Remove sections that show sun damage or feel brittle. These might be salvageable for carding, but often, they are not worth the effort.

Picking: Weak spots often show up here. If locks crumble in your hands, it's best to remove them.

Scouring: Gentle washing may release broken bits into the rinse water.

Combing/Carding: Avoid drum carders for fleeces with breaks; they can tangle short bits and create neps. Combing is better for separating sound fibers from the weak.

Spinning: If you're using fiber with some breakage, spin it with a higher twist than usual.

Short Fibers or Second Cuts

Short fibers can come from second cuts during shearing or naturally short staple breeds. These can cause pilling, neps, or weak spots in yarn.

Skirting: Look for short, fluffy pieces and remove them. Flip the fleece cut side up to spot second cuts more easily.

Picking: Short fibers will often fall away during this stage. Save them for felting or texture work.

Scouring: Nothing special required.

Combing/Carding: Use combs to separate longer staples. Shorter bits can be saved for woolen-style spinning.

Spinning: Short fibers need more twist to hold together. A woolen spin with long draw can turn them into soft, lofty yarn.

Matting or Felting

Matting can happen on the sheep or during washing if agitation or temperature changes are too harsh.

Skirting: Remove severely felted parts. In the past, matted wool was sometimes repurposed for padding or outerwear.

Picking: Tease apart locks gently. If they resist, set them aside for felting rather than spinning.

Scouring: Keep water hot but avoid agitation. A long cold soak (suint method) beforehand can help loosen fiber.

Combing/Carding: Flick or comb matted areas. Use study tools for the first round. You wouldn't want to risk your super-fine combs until you have gotten the matts or felted sections out.

Spinning: Matted wool may still be usable with effort, but can resist drafting. Try blending or use for core spinning.

Scurf

Scurf is a dandruff-like skin flake that clings to fiber. It doesn’t wash out easily and can be very stubborn.

Skirting: Heavily scurfy areas may be worth removing. In historical spinning communities, visible scurf could devalue wool.

Picking: Flick or tease open locks. Avoid shaking scurf from butt to tips, or the flakes can fall deeper into the wool.

Scouring: Vinegar rinses might help, but scurf is rarely removed by washing alone. Enzyme soaks have mixed results.

Combing/Carding: Flicking or combing can help, but avoid drum carders which push scurf deeper into the fiber. Try using a super fine comb, such as a flee comb, to comb out the scruff and wipe it on a towel kept on your knee between passes.

Spinning: If scurf remains, you can spin it anyway for rustic use, but it will be visible in the finished yarn.

Odor

All raw fleece smells like sheep, but strong or foul odors may suggest something more concerning. Some odors can be from a dirty sheep, bacteria in the unwashed wool, or pests. However, using the suint method of cleaning may also give wool a foul smell.

Skirting: Remove fleece with manure or heavy urine contamination.

Picking: Sunlight and fresh air can do wonders. Lay the fleece out to breathe before scouring.

Scouring: Use vinegar in rinse water to neutralize odor. Essential oils (like lavender) are optional but pleasant.

Combing/Carding: Odor should be gone by now. If not, rewash lightly and dry thoroughly. Lay out in the sun for more of a reduction.

Spinning: If residual odor lingers during spinning, plan to rewash the finished yarn, which can stand hotter water and detergents than raw wool.

Bugs or Other Pests

Raw fleece can harbor moth eggs, beetles, or other pests if improperly stored.

Skirting: Freeze fleece for 48 hours or heat above 120°F before storage. Keep it sealed when not in use.

Picking: Wear gloves if you're concerned. Cold soaking beforehand can ease your mind.

Scouring: Hot water and detergent should kill anything remaining.

Combing/Carding: Inspect tools and workspace to ensure nothing has transferred.

Spinning: Keep your stash and finished yarn safe by storing in airtight containers.

Staining

Stains come from urine, manure, or sun exposure and are common in raw fleece. While they don’t always affect structure, they can affect dyeing and appearance. Canary staining can come from bacteria, as well.

Skirting: Remove heavily stained sections if desired.

Picking: Stained fiber might still be usable if sound. Open locks and evaluate staple strength.

Scouring: Soak in a long, warm vinegar bath or use oxygen bleach (not chlorine) if needed. Some stains may be permanent.

Combing/Carding: Evaluate how visible the stain is. It may blend well in batts or roving.

Spinning: Stained yarn can be overdyed, used in tweeds, or reserved for non-garment projects.

Final Thoughts

Processing raw fleece by hand is an act of deep connection to the land, the animal, and the traditions of fiber craft. Historically, no usable fiber was wasted. Even challenging fleeces were turned into rugs, stuffing, or coarse cloth. Today, we can afford to be a little more selective, but there is still great value in learning to troubleshoot and transform raw wool.

Whether you're spinning yarn for a shawl, felting ornaments, or teaching a class on historical textiles, knowing how to handle each issue empowers you to get the best from your fiber. With time and experience, you'll not only improve your skills, but you'll start seeing "problem fleeces" as creative opportunities.

Let me know if you would love a video or more detailed explanation on any of these steps!