Homespun on the Southern Frontier: Everyday Cloth in a Changing World

Homespun on the Southern Frontier: Everyday Cloth in a Changing World

When we think of the early American frontier, images of log cabins, rugged landscapes, and self-reliant families often come to mind. If we imagine clothing, it might be dirty, worn, or ragged, conceptions shared by urban and literate populations of the time. Between the 1790s and the 1830s in the developing settlements of western Tennessee, northern Alabama, and eastern Arkansas, homespun was not simply a household necessity. Homespun yarn and cloth was a cultural marker that set frontier families apart from urban Americans and from the wider world.

A Fabric of Necessity

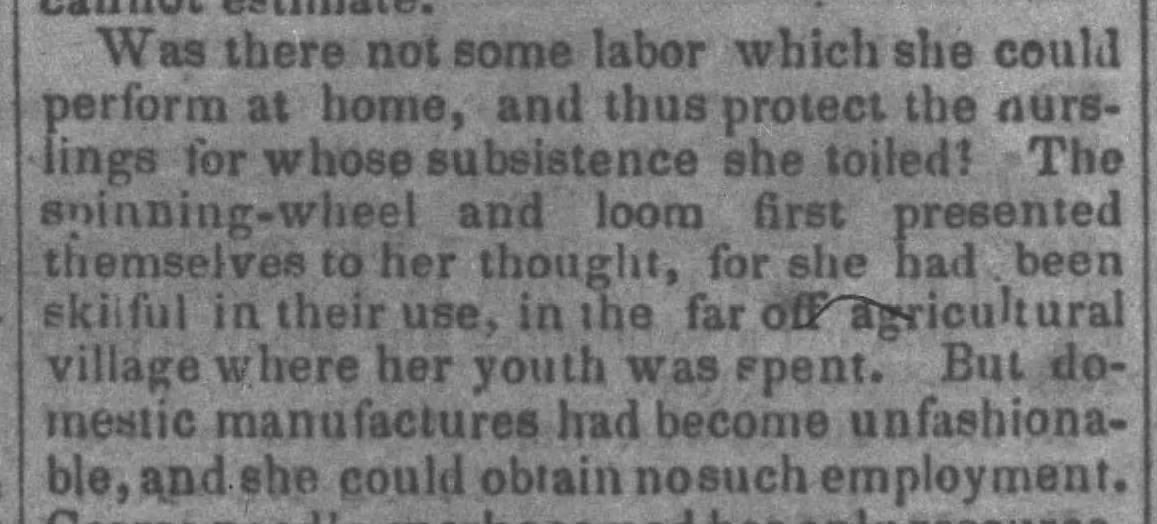

On the Southern frontier, store-bought fabrics were often hard to come by and perhaps more expensive than many could afford. Settlers often relied on home production to meet daily needs. Spinning wheels, looms, and dye pots were fixtures in most households.

Memoirs from the region describe women weaving wool, cotton, and flax into cloth for everyday use. Loom houses, small outbuildings dedicated to weaving, were common across the countryside. Descriptions of these structures, and of the constant work inside them, appear repeatedly in family histories and personal narratives.

These processes demanded skill and time. A family’s annual supply of clothing depended on the diligence of its spinners and weavers, both free and enslaved. The production of cloth was a form of survival labor, as essential as tending crops or raising livestock.

Economic Variation in Homespun

Not all homespun looked the same. Economic background shaped both the quality of cloth and the extent to which families relied on store goods. The equipment available in each household, the type of fibers at hand, and the skill of the family members, or enslaved workers, who produced the cloth all played a role in shaping how people dressed.

Subsistence Farmers: Simple Tools, Practical Cloth

For subsistence farmers, textile production was a task of necessity carried out with minimal equipment. A single great wheel for spinning wool or flax, a few hand cards, and a sturdy loom often housed in a shed or corner of a cabin were all that most families could afford. The products of these modest setups were coarse but serviceable: cotton-linen blends for everyday shirts, linsey-woolsey woven from wool and flax for winter garments, and clothing dyed with walnut hulls or other natural dyes readily available in the landscape.

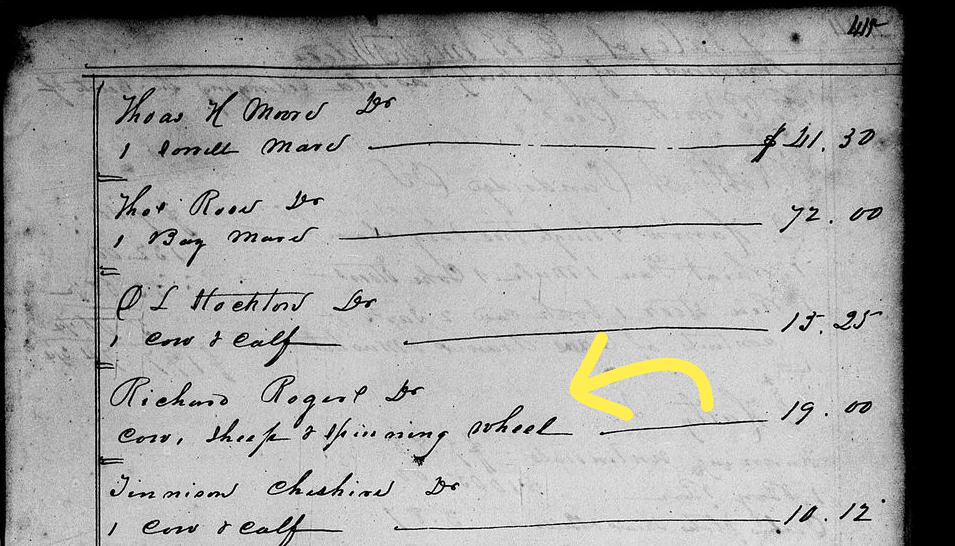

Probate records from western Tennessee in the 1820s often list “1 spinning wheel” or “1 loom” among the most valued household goods, underscoring how essential even a single set of tools was for survival. In Old Times in West Tennessee, the author recalled that “every man, woman, and child wore homespun,” a phrase that conveys both ubiquity and necessity for farming families. These were households where textile work consumed long hours and left little room for ornamentation.

Middle-Tier Households: Blending Homespun with Store-Bought

Families with modest surplus income often invested in more than one wheel, perhaps a flax wheel for fine spinning, a great wheel for wool, and a reel for winding yarn. Some kept a dedicated loom house on their property, a sign of both the volume of work being produced and the family’s relative prosperity. These households were still dependent on homespun for daily wear, but they might purchase a few yards of calico or factory cloth from a dry goods store in a nearby town. Brightly printed cottons or lighter muslins were often reserved for Sunday wear, children’s dresses, or trimmings on garments otherwise made from homespun.

A memoir from the early settlement period of middle Tennessee describes young women working “by the firelight at the wheel,” while a loom in the outbuilding produced the family’s bed ticking and everyday cloth. These glimpses suggest a pattern: middle-tier households balanced the labor of spinning and weaving with a cautious use of store goods, investing money only where the most visible or socially important garments were concerned.

Wealthier Settlers: Variety and Display

Wealthier settlers, particularly those with larger landholdings or professional occupations, had access to a greater range of textile tools and the ability to employ others to use them. Inventories from these families sometimes list multiple looms, reels, and wheels, indicating that production was carried out on a larger scale. In many cases, enslaved women were tasked with spinning and weaving, producing cloth for both the family and the plantation workforce.

These families could also afford imported fabrics. Dry goods merchants in river towns such as Memphis or Natchez advertised silks, satins, and fine woolens brought in by flatboat or wagon. Such cloth was used for dresses, coats, or other garments that signaled wealth and refinement. Yet even in prosperous homes, homespun retained a role. Servants and enslaved laborers were almost always clothed in domestically produced fabric, and family members might continue to wear homespun for work garments.

An 1830s account from Bolivar, Tennessee, for example, notes the contrast between the “Sunday attire of imported calicoes” and the weekday reliance on “the strong home-woven stuff that never failed in service.” For wealthier settlers, the loom house remained a place of industry, but one that supported social display rather than mere survival.

Homespun as Supplemental Income

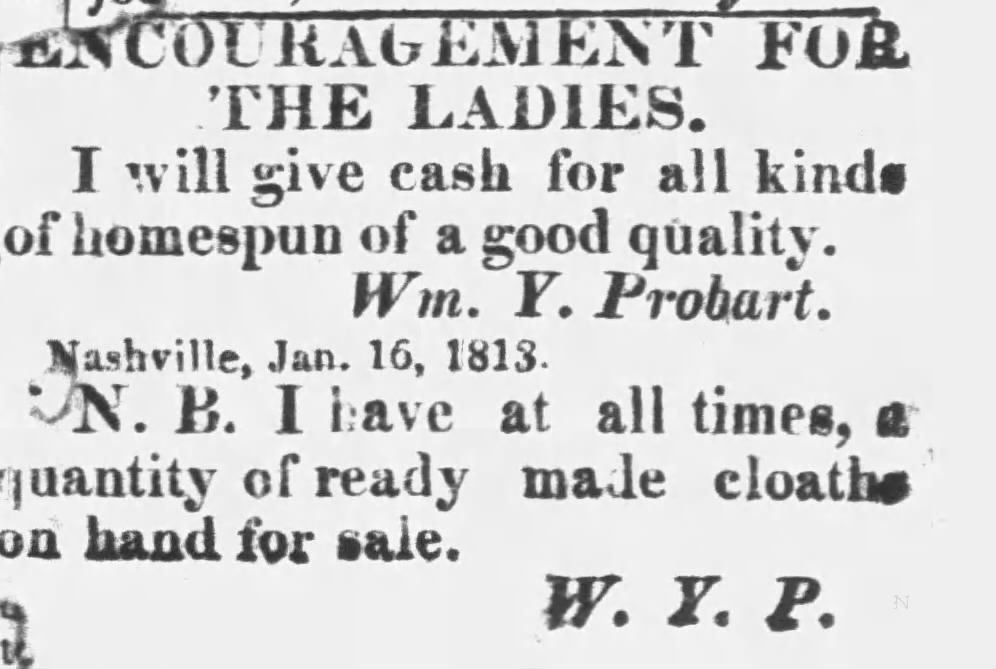

Across all economic classes, spinning and weaving could also serve as a means of generating extra income. Dry goods merchants frequently advertised their willingness to purchase homespun yarn or cloth, particularly when cotton was scarce in local markets. Women who produced more cloth than their families required could exchange it for credit or trade it for imported goods.

This practice underscores how deeply textile work was integrated into the local economy. Homespun was not just a marker of domestic diligence, it was a form of currency. Wills and probate records listing spinning wheels, loom houses, and inventories of “homespun” make clear that cloth was treated as an asset, as valuable to the estate as livestock or tools.

The Cost of Cloth: Homespun, Domestic, and Imported

Textile choices on the frontier were not simply a matter of taste or skill; they were also shaped by cost. Surviving store ledgers, newspaper advertisements, and account books from the early nineteenth century reveal the wide gulf between the price of homespun and the price of store-bought cloth.

- Homespun Cloth: Homespun was, in one sense, “free,” since it came from a family’s own labor and raw materials. Yet the time required was immense: spinning a pound of wool or flax into usable thread might take 40 hours or more, and weaving it into cloth consumed additional days. In probate inventories from Hardeman and neighboring counties, finished homespun cloth was sometimes valued at 25 to 40 cents per yard. Adjusted for inflation, this equals roughly $7 to $12 per yard today. The low market value reflects how commonplace it was, even though the labor investment was enormous.

- Domestic Factory Cloth: By the 1820s and 1830s, American mills in New England were sending “domestic cloth” into western markets. Advertisements in Memphis and Nashville papers list coarse cottons at 12 to 20 cents per yard and finer shirtings at 25 to 35 cents. In today’s money, that range is $3.50 to $10 per yard. For families near river ports, factory cloth could compete with or even undercut the market price of homespun, though the cash outlay made it a luxury for poorer households.

- Imported Fabrics: Silks, fine muslins, and calicoes imported from Europe or India were far more expensive. In 1820s advertisements, printed calicoes often cost 50 cents to $1 per yard (about $15 to $30 per yard today). Silks and satins ran even higher. These were fabrics of display, affordable only to wealthier settlers, and worn primarily for special occasions.

The comparison underscores why homespun endured on the Tennessee frontier. For a family living on subsistence farming, paying the cash equivalent of twenty or thirty modern dollars for a single yard of calico was out of reach. Homespun allowed families to clothe themselves with the resources at hand, even if it meant sacrificing refinement or variety.

Local Views: Respect and Practicality

Within these frontier communities, wearing homespun was not a mark of shame. It was a badge of industry and respectability. To appear in town clothed in fabric your household had produced showed diligence and resourcefulness. Young women were judged by their ability to spin even yarn and weave sturdy cloth, and their skill was often considered as important as their cooking in shaping household reputation.

Clothing was made for durability. Garments were patched, redyed, and reworked to extend their life. Practicality carried more weight than fashion. In the culture of the Southern frontier, homespun was not only accepted but expected.

Regional and National Perceptions

Beyond the frontier, perceptions shifted.

- In southern cities such as Charleston or New Orleans, factory-made fabrics and imported silks signaled refinement. To urban elites, homespun often appeared rustic or backward.

- In the North, factory cloth was widely available by the 1810s. Wearing homespun in Boston or New York suggested provincial roots.

- Nationally, homespun carried political resonance. During the Revolution and again during the embargo years of the early 1800s, Americans praised homespun as patriotic. But by the 1820s, it had become increasingly associated with rural necessity rather than national pride. Newspapers often characterized those who wore homespun in fiction, satire pieces, or politically commentary.

These shifting perceptions meant that what was a daily uniform for Southern settlers could be read elsewhere as evidence of poverty or backwardness.

Conclusion: The Meaning of Homespun

Homespun on the southern frontier was more than cloth. It was identity. It signified respectability and labor within the community, provincialism in the eyes of urban elites, and resilience in the face of global economic transformation. In southwestern Tennessee during the 1790s through the 1830s, homespun reveals the tension between local necessity and global change.

Through memoirs that recall loom houses, patched garments, and the ubiquity of homemade cloth, we glimpse the everyday textures of frontier life. For these families, survival was spun and woven by hand, one thread at a time.

Bibliography

Memoirs and Regional Histories

- Brown, Thomas Menees. Old Times in West Tennessee: Reminiscences Semi-Historic, of Pioneer Life and the Early Emigrant Settlers in the Big Hatchie Country. Memphis: Cossitt Library, 1873. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/oldtimesinwestte00will_0.

- Crockett, David. A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee. Philadelphia: E.L. Carey and A. Hart, 1834.

Newspapers and Advertisements

- Nashville Whig (Nashville, TN). Advertisements for dry goods including calicoes, shirtings, and spinning wheels. 1820s–1830s. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

- Memphis Enquirer (Memphis, TN). Advertisements for domestic cloth, homespun purchases, and imported fabrics. 1830s. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

Periodical Articles

- The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London: Charles Knight, 1836. “Household Spinning-Wheels and the First Spinning Machines.”

Material Culture and Museum Collections

- Carlin, Elizabeth (attrib.). Overshot Coverlet, Tennessee, c.1820–1830. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. https://www.si.edu/object/elizabeth-carlin-attr-overshot-coverlet-c-1820-1830-tennessee%3Anmah_214178.

- Daughters of the American Revolution Museum. “Homespun Support” featured object: Men’s homespun coat, c. 1805–1810. Washington, DC. https://www.dar.org/museum/featured-object/homespun-support.

- University of New Hampshire, Irma Bowen Historic Clothing Collection. “Dress, blue and white striped linen, homespun, c. 1800.” Durham, NH. https://www.library.unh.edu/find/collections/irma-bowen-historic-clothing-collection.

- Fashion Archives & Museum of Shippensburg University. “Boy’s Jacket, homespun wool, c. 1795–1810.” Shippensburg, PA. https://fashionarchives.org/the-revolution-of-fashion/