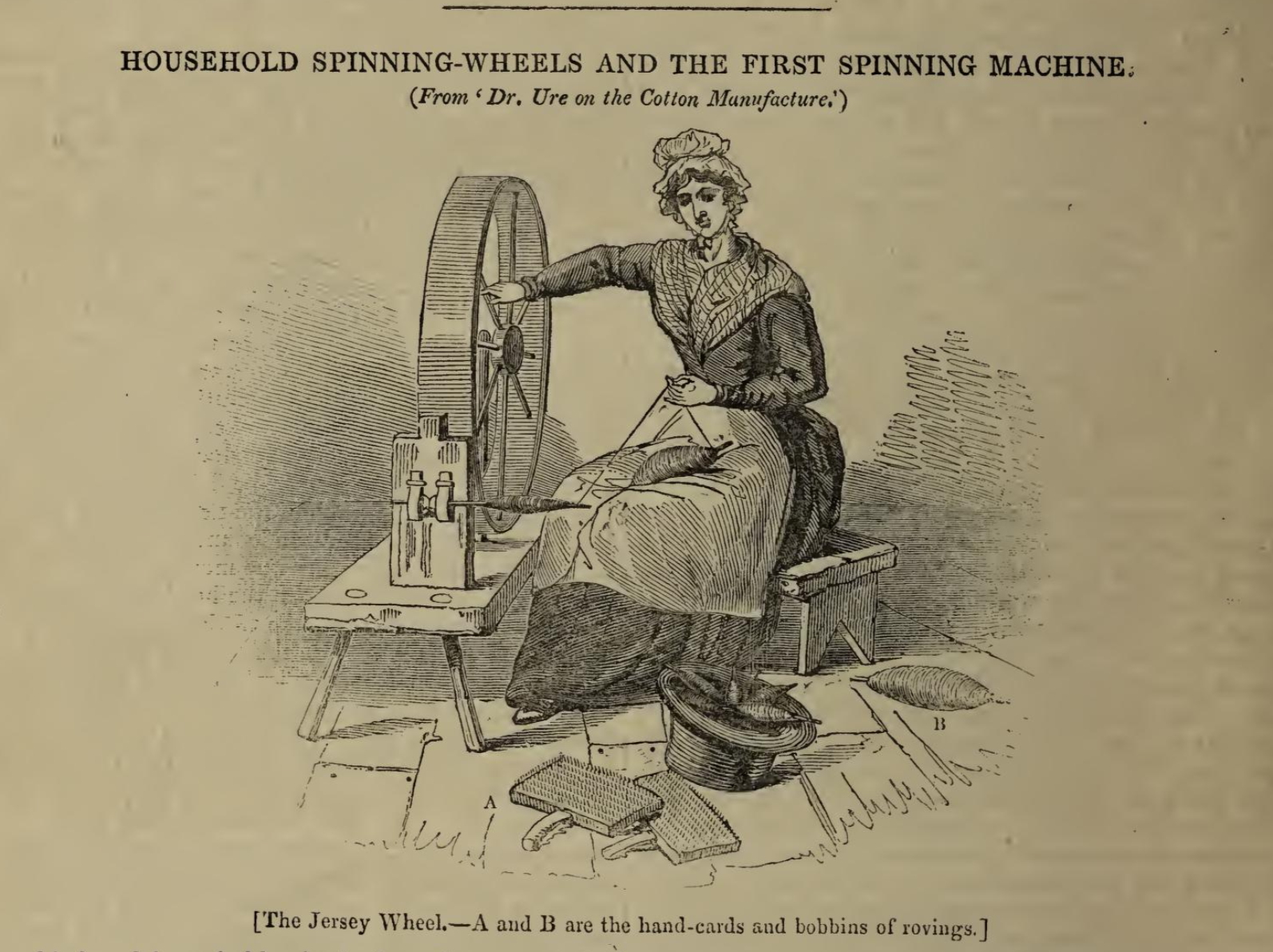

Why Sourcing Local Wool is Essential for Spinners: Benefits, Tips, and Resources

Support your local shepherds and reduce your carbon footprint in the fiber craft sector

When it comes to spinning and fiber crafts, the materials you choose can make all the difference in your final product. One of the best decisions you can make as a spinner or fiber crafter is to source your wool locally. Not only does this choice support your craft, but it also has significant benefits for your local community and the environment. In this blog post, I’ll explore the importance of sourcing local wool, the benefits it offers, and resources to help you find the best local wool for your fiber projects, as well as some of my personal experiences.

Why Sourcing Local Wool Matters

Supporting Local Farmers and Shepherds

One of the most compelling reasons to source wool locally is the direct support it provides to local farmers and shepherds. By purchasing wool from nearby farms, you contribute to the sustainability of small-scale agriculture. These farms often prioritize animal welfare and sustainable farming practices, ensuring that the wool you use is of the highest quality.

Local farmers often have a difficult time making a living wage from their herds, as they typically have more overhead costs for smaller yields. Therefore, their products must be priced to net a profit, often much higher than commercially processed fibers.

When I first started spinning, I had no idea where to get fiber. I found a local shepherd selling their freshly shorn whole fleeces for $20 a piece. I bought one, and while it was difficult to clean and process, I learned a lot through the experience. Since, I have purchased several other fleeces, all of varying qualities, finding that no matter how much vegetable matter (VM), or dirt, with a little elbow grease, you can produce a wonderful finished yarn.

Preserving Local Breeds and Biodiversity

Many local farms raise heritage breeds that are well-suited to the climate and terrain of their region. By sourcing wool from these farms, you help preserve these breeds and the biodiversity of your local ecosystem. Each breed’s wool has unique qualities that can add distinct characteristics to your spinning and crafting projects.

Sourcing wool locally significantly reduces the carbon footprint associated with transportation. Wool that travels shorter distances from farm to spinner means less fuel consumption and fewer emissions. Additionally, local farms are more likely to use environmentally friendly practices, such as rotational grazing, which contributes to healthier soil and reduced erosion.

I purchased some Leicester Long Wool combed top from Wild Rose Farms on Whidby Island. This beautiful wool had a super long staple length and spun into a smooth, thin, lace weight worsted yarn. I never would have discovered this fiber if it were not for the Shave 'Em to Save 'Em program, promoting local flocks.

The Benefits of Using Local Wool in Fiber Crafts

Connecting to your Community

Using wool from your local area can deepen your connection to your craft. Knowing the story behind the wool—where it came from, how the sheep were raised, and who produced it—can add a meaningful layer to your work. This connection can also inspire creativity and pride in the pieces you create.

I love that I can pull out a local fleece and know the name of shepherd, even know the actual sheep it came from.

Supporting the Local Economy

When you purchase local wool, you’re investing in your community. The money you spend stays within your local economy, supporting not just the farmers but also local businesses that may rely on agriculture. This economic boost can help sustain rural communities and keep traditional crafts alive.

However, a lot of shepherds, I have found, often give away their fleece for free because they don't want to put the time or effort into finding where to sell their fleece, or they don't have the resources to produce a high quality fleece, such as coating the sheep. I think the biggest reason, though, is that many local shepherds just don't have the connections or community to know that there is a market for their fleece.

How to Source Local Wool: Resources and Tips

Local Farmers’ Markets and Craft Fairs

Farmers’ markets and craft fairs are excellent places to start your search for local wool. Many small farms sell their wool directly at these events, allowing you to see and feel the product before purchasing. This direct interaction with the producers also gives you the chance to ask questions about their farming practices and the specific qualities of their wool.

Fiber Festivals

Fiber festivals are another great resource for sourcing local wool. These events are typically focused on all things fiber-related and attract vendors from the surrounding area. Attending a fiber festival can also be a fantastic way to network with other spinners and fiber crafters, exchange ideas, and learn more about local wool sources.

Online Directories and Marketplaces

Several online platforms and directories can help you find local wool producers. Websites like the Livestock Conservancy and LocalHarvest offer searchable databases of farms and markets where you can find local wool. Additionally, platforms like Etsy have sellers who offer wool from small farms, often with detailed descriptions of the wool’s origin.

I have found huge success with Facebook groups, such as "Raw Wool for Sale" or "Dirty Fleece, Done Dirt Cheap." While many of these groups are nationwide (in the US), you can search for or connect with individuals close to you.

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA)

Some farms offer wool shares through Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) programs. By purchasing a wool share, you receive a portion of the farm’s wool production for the year. This arrangement not only ensures you have a steady supply of local wool but also builds a strong relationship between you and the producer.

Farm Visits and Wool Tours

Consider arranging a visit to a local farm or participating in a wool tour. Many farms welcome visitors and offer tours where you can learn about the wool production process from start to finish. This hands-on experience can give you a deeper appreciation for the wool you use and the work that goes into producing it.

I loved being able to visit the Tahoma Mills Alpaca Farm, especially because I loved meeting Deli, a pregnant alpaca who loved snacks (and I was pregnant at the time, too). I was able to purchase some of the yarn Tahoma Mills spun from Deli's last fleece.

Start your journey today by exploring the local wool producers in your area, and enjoy the unique qualities that local wool brings to your fiber crafts. Feel free to reach out if you want any help getting started!