Patsey Williams: A Case Study of a Southern Frontier Textile Maker

Clothing for the First Settlers

Meta description: Explore how early Tennessee settlers like Martha “Patsey” Williams spun, wove, and dyed their own homespun cloth from 1790–1840. Discover the tools, fibers, and changing social meaning of handmade textiles on the southern frontier.

Imagine you are packing for an extended vacation to a remote location, somewhere without shops or access to same-day delivery for online shopping. What would you pack? Enough of your favorite shampoo, or enough shirts and underpants to last you, depending on whether you have access to a clothes washer.

Now, imagine instead you are packing all these items into a wagon with your family, heading into an unknown land where you do not know when you might see a store. Such was the case of many early settlers to the southern frontier.

Joseph S. Williams wrote in his account, Old Times in West Tennessee: Reminiscences - Semi-Historic - of Pioneer Life and the Early Emigrant Settlers in the Big Hatchie Country (Memphis: W.G. Cheeney, 1873):

“When the emigrants came to West Tennessee, they brought with them a year’s supply of provisions and such household and farming implements as could be transported in a wagon — axes, plows, spinning wheels, looms, and such other tools as were indispensable to frontier life.”

The disclaimer must be made that, although Joseph claims to be a descendant of one of the first settlers, it is also noted in the preface that it was “written hurriedly and without sufficient data.” Joseph goes on to describe how, in the early 1800s, his father “pitched a tent and called it home.” Before setting out, they purchased “everything requisite to a comfortable living in the wilds of the Big Hatchie,” including “cards, cotton, and spinning-wheels.” He also describes how his mother ensured everyone, including white family members and enslaved black people, was fitted with homespun clothes, such as “stout overcoats for the men and long jackets for the women.”

The family settled in Fayette County, Tennessee, just east of Memphis and south of the Big Hatchie River. This account easily shows the responsibility for clothing falling on the wife and mother of the head of household. Taking note of their textile-making supplies, such as the cards, cotton, and spinning wheel, we can infer that Martha “Patsey” Williams, née Seawell, likely spun and wove cotton herself—likely with the assistance of her enslaved household members and daughters—enough cloth to make up some portion of the clothes the family wore.

While they brought some cotton with them, the narrative later states that one of the first plantings they made at their new home was a small patch of cotton for domestic use. The account also describes how they purchased a gin made by a local man, Joshua Farrington, whose quality of work rivaled that of other well-known gin makers in more settled parts of Alabama. In this whole story, it segues into how a screw cutter was needed for the mill, and how this screw cutter’s wife and children were brought to stay in the loom-house on their property, as the family would not need the building until the cotton was picked and ginned. So important was the need for a home for the loom that the building was constructed and furnished before the family could even harvest the first crop of cotton.

Toward the end of the account, Joseph writes about his mother’s life nearer to her passing, describing her as a woman “who spun cotton and wove cloth.” Such was the worth of her work that the author felt the need to recount it in the measure of her life.

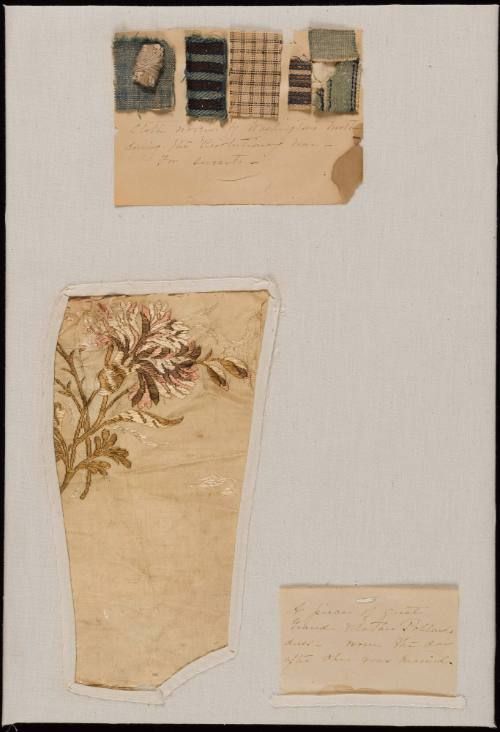

Martha, also known as Patsey, was born in 1790 in Warren County, North Carolina, to families who had lived in the state or neighboring states for many generations. She would have learned to card, spin, and weave as a young girl during an era when homespun cloth was extremely fashionable and patriotic (Ulrich, The Age of Homespun , 2001) and when textile work was considered a marker of industrious virtue.

One might imagine Patsey’s home filled with the quiet industry of spinning and weaving—the hum of the wheel, the rhythm of the loom, the smell of scoured cotton drying by the hearth. The 1790s through 1820s were an age when nearly every rural household in North Carolina produced at least part of its own textiles. During these eras, a good spinner might be able to spin several skeins of yarn or thread per day, and a good weaver might weave five to ten yards of cloth in a week. Most often, these “good” craftspeople were the same woman, or several of the same women in their household.

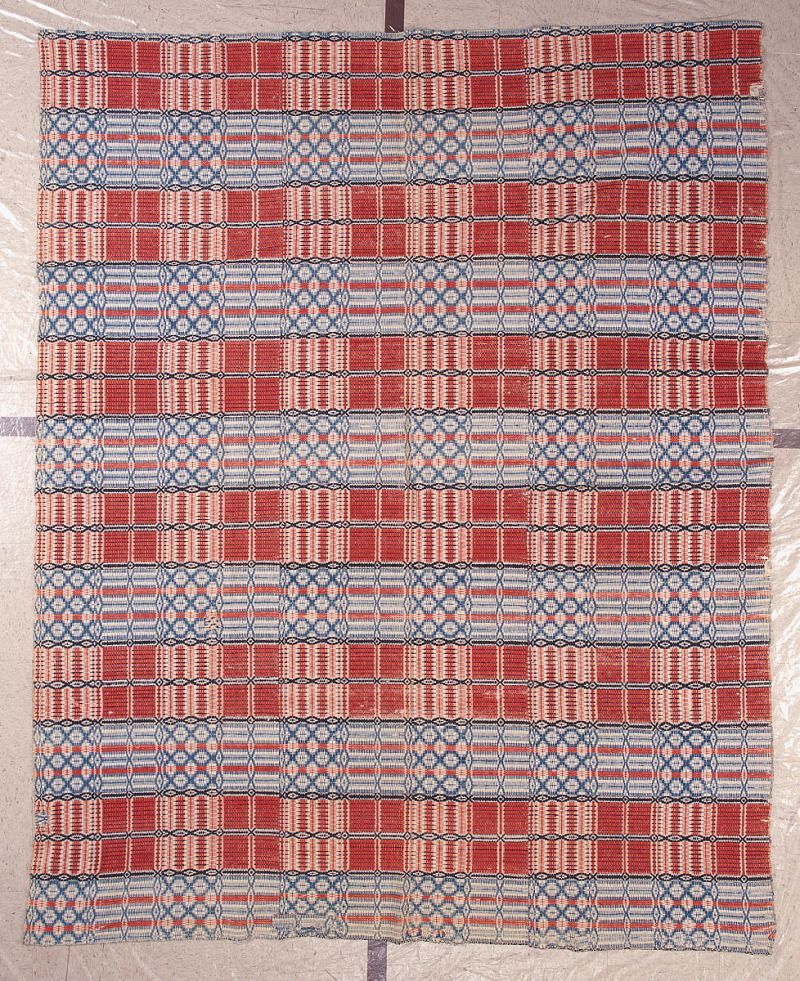

Surviving examples of early southern homespun include cotton-linen checked aprons, wool linsey skirts, and handwoven coverlets, which show both creativity and thrift. Some were dyed with walnut or madder root, others with indigo bought by the ounce from local merchants (Colonial Williamsburg Textile Collection; Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts). Each yard of cloth Patsey or her household produced represented time saved, cash spared, and security ensured in a world where store goods might be months away by wagon or flatboat.

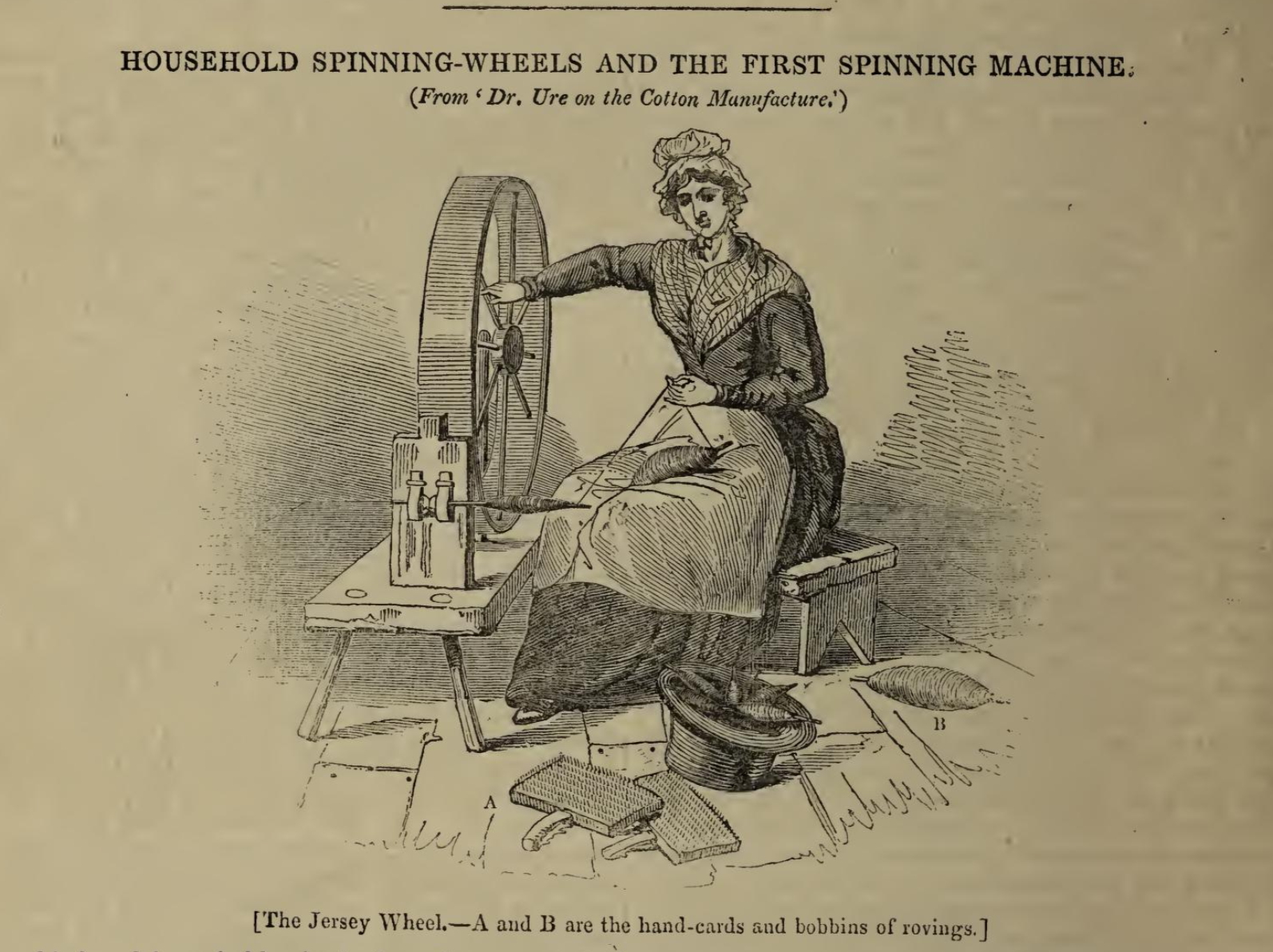

Most cloth on the Tennessee frontier was produced within the household using a combination of hand tools and simple machinery that had changed little since the colonial period. Spinning was typically done on the great wheel, or walking wheel, for wool and cotton, and on the Saxony or treadle wheel for flax and finer yarns. Once spun, the women would wind yarn or thread onto reels, size it with starch to strengthen it, and warp it onto narrow floor looms. These looms were operated entirely by foot treadles and hand shuttles, and often produced plain, twill, or simple checked weaves. The resulting fabrics were serviceable rather than refined: sturdy cotton-linen “domestic” cloth for shirts and trousers, wool and linen blends for winter wear. Contemporary observers described this homespun as “durable and strong, though coarse,” fit for daily use in both white and enslaved households.

Surviving southern examples show subdued stripes, small checks, and natural dyes derived from walnut hulls, sumac, or indigo. Such cloth rarely approached the evenness of factory-made goods. However, its irregular texture and hand-dyed hues reflected the skill, resourcefulness, and aesthetic sense of the women who made it.

By the 1830s, industrial mills in places like Lowell, Massachusetts, were transforming spinning and weaving into waged labor. In the Southern frontier, household textile production persisted, even as imported goods became more accessible through new stores in Bolivar, Jackson, and Memphis. Many families continued to spin and weave at home, either due to the cost of commercial cloth, pride in their work, or the difficulty of obtaining said goods. However, over the decades, homespun became increasingly relegated to the lower class or the enslaved population.

Factory-woven calicoes and printed muslins became available in river towns and crossroads stores, advertised alongside imported ribbons and shawls from New Orleans or Philadelphia. To wear homespun was no longer a fashionable choice but a mark of remoteness. In many Tennessee households, factory cottons began to appear in Sunday dresses or children’s clothes, while coarse homespun was increasingly reserved for enslaved people, field laborers, and everyday work garments. Yet even as its social prestige declined, home manufacture persisted. Families still needed sheets, towels, and rough work clothes; enslaved women still spun and wove for plantation needs; and in more isolated upland regions, the wheel and loom remained as essential as the plow.

By the 1840s, the whir of spinning wheels and the steady beat of looms were fading from many Tennessee households. As railroads extended inland and store goods became easier to obtain, factory cloth increasingly replaced handwoven fabric in everyday life. For younger women raised in this new consumer era, the skills their mothers had prized—spinning, weaving, dyeing—became symbols of an older, more laborious way of life. Yet even as homespun lost its place in fashionable wardrobes, it never disappeared entirely. In many rural communities, particularly in the hill country of Middle and East Tennessee, families continued to weave sturdy cotton and wool fabrics for household use well into the 1850s.

The decline of homespun was not a disappearance but a transformation. What had begun as a necessity became a memory, a symbol of endurance and the unrecorded labor of women whose work clothed a frontier and shaped a region’s identity.

Sources

- Joseph S. Williams, Old Times in West Tennessee: Reminiscences Semi-Historic of Pioneer Life and the Early Emigrant Settlers in the Big Hatchie Country (Memphis: W.G. Cheeney, 1873), 13, archive.org.

- Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001).

- Catherine E. Kelly, Fashioning American Femininity: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Early Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999).

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Woman’s Dress, Homespun Cotton, Early 19th Century , accession no. 1991-275, Colonial Williamsburg.

- Florence M. Montgomery, Textiles in America, 1650–1870 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1984), 392–96.

- Clive L. N. Smith, Textile Production in the Southern Backcountry, 1780–1830 (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina, 1988), 77–81.

- Advertisements, Western Tennessee Republican (Bolivar, 1826), and American State Papers , vol. 5 (1827–1834).

- Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988).

SEO Keywords

homespun cloth, Tennessee frontier, pioneer textiles, early American spinning, frontier weaving, women’s labor history, Big Hatchie River, 19th-century homespun, domestic textile production